Crypto Faces Liquidity Endgame—Debt And Inflation Risks Mount By 2026

Raoul Pal’s latest “Journey Man” episode brings back Michael Howell, CEO of CrossBorder Capital, for a sweeping tour of the liquidity landscape that has propelled risk assets like crypto for nearly three years. Both agree the global liquidity cycle is “late,” still advancing but increasingly mature, with its eventual peak most likely pushed into 2026 by policy engineering, bill-heavy issuance, and rising use of private-sector conduits.

The investment implication running through the conversation is unambiguous: long-duration assets—crypto and technology equities—remain the primary beneficiaries of ongoing currency debasement, yet the endgame is now visible on the horizon as a wall of debt refinancing and inflation risk approaches.

How Long Will The Liquidity Cycle Push Crypto Higher?

Howell’s high-level assessment is stark. “We’re late. It’s not inflecting downwards yet—we’re still in an upswing—but… the liquidity cycle is about 34 months old. That’s pretty mature.” In his framework, cycles typically run five to six years. Pal’s Everything Code—a synthesis of demographics, debt, and the policy liquidity needed to roll that debt—arrives at a similar destination, albeit with a slightly shorter cadence and a crucial timing nuance.

“My view is it’s been extended,” Pal says, adding that the peak “normally would have finished sometime this end of this year, but it feels like it’s going to push out.” Howell places the likely turn “around about early 2026,” with his model’s latest estimate at March 2026, while Pal is “in the camp of Q2” 2026. The difference is tactical; the thrust is the same: the late-cycle rally can run further, but investors are now operating inside the final act.

At the center of that act is what Howell calls a structural transition “ from Fed QE to Treasury QE .” The US Treasury’s heavy tilt to short-dated bills over coupons lowers the average duration of paper held by the private sector. “Very crudely, we tend to think that liquidity is equal to an asset divided by its duration,” Howell explains.

Reducing duration mechanically boosts system liquidity. That issuance profile also corrals volatility and creates powerful bid auras: banks gladly absorb bills to match deposit growth, and, increasingly, so do stablecoin issuers managing cash to T-bill ladders. “If any credit provider buys government debt—particularly short-dated stuff—it’s monetization,” Howell notes. The result, in Pal’s summary, is that policymakers have shifted from balance-sheet expansion to a more complex “total liquidity” regime, where banks, money funds, and even crypto-native entities become the delivery rails of debasement.

The debate over near-term Fed liquidity hinges on reserves and the Treasury General Account. The quarterly refunding blueprint has telegraphed a rebuild of the TGA toward the high-hundreds of billions. Howell is unconvinced it happens quickly or fully, because draining that much cash would risk a repo spread spike, something the Fed and Treasury appear determined to avoid.

“Everything I hear… is they want to manage that liquidity. They don’t want to pull the rips on the markets,” he argues, adding that the Fed has effectively been targeting a minimum level of bank reserves since last summer’s stress-test changes. “The Federal Reserve controls bank reserves in aggregate completely,” Howell says. Even if the TGA edges higher, “you can find other ways of injecting liquidity… through Treasury QE or getting the banks to buy debt.”

Global Liquidity Remains Strong

The global overlay is every bit as important. Europe and Japan, as Howell frames it, are net-adding liquidity; China has moved decisively to ease via the PBoC’s toolkit—repos, outright OMOs, and medium-term lending—after a stop-start attempt in 2023.

Chinese 10-year yields and term premia have started to firm from depressed levels, which, paradoxically for asset allocators, “can be good” if it signals escape from debt-deflation toward reflation and a commodity up-cycle. “If you get this big Chinese stimulus continuing… that should mean stronger commodity markets,” Howell argues, with Pal adding that a revived China would restore the missing engine of the global business cycle even as liquidity remains the dominant market driver.

Japan is the outlier with a fascinating twist. Disaggregating term premia shows the selling is concentrated in the ultra-long end, not the belly or front of the curve. Howell’s inference is a duration rotation rather than a full-curve sovereign dump—“a switch from bonds into equities”—consistent with mild-inflation regimes that favor stocks. Why tolerate it?

Howell floats two possibilities: Japan “actually want[s] some inflation,” which quietly erodes debt burdens, and, more speculatively, “the Japanese are being told to ease monetary policy by the US Treasury,” keeping the yen weak to pressure China. He is careful to caveat, but the pattern—persistent yen weakness despite strong equity inflows—fits the policy-coordination narrative that Pal has long emphasized.

The U.K. and France, by contrast, look like textbook supply-shock sovereigns. Here, term premia have risen across the curve, reflecting heavy issuance, swelling welfare-state obligations, and weak growth. Howell highlights that the U.K.’s “underlying term premium [is] up over 100 basis points in the last 12 months,” a move that cannot be waved away as a single budget misstep.

The policy menu is narrow: higher taxes, eventual spending restraint (likely only enforced by a crisis or an IMF-style conditionality), and, ultimately, some form of monetization—whether relabeled QE, regulatory loosening to stuff more gilts into bank balance sheets, or de-facto yield-curve management. “Let’s not say never for [monetization] because that’s almost inevitably what’s going to happen,” Howell says.

Hovering over all of it is the dollar. On Howell’s preferred real trade-weighted lens, the dollar remains in a secular up-channel with a cyclical correction in train. Rest-of-world balance-of-payments data still show net inflows to the dollar system.

Pal and Howell agree that the administration wants a weaker dollar cyclically to ease the refinancing of the roughly half of global debt that is dollar-denominated, even if the dollar remains “fundamentally strong” as the world’s primary collateral system. That’s the paradox Pal underscores: “A weaker dollar allows people to refinance their debts… That ends up being the debasement of currency, even though you get dollar inflows.”

In that debasement regime, both men argue, long-duration, liquidity-sensitive assets lead. “You’ve got to start thinking about how to invest in the monetary inflation world,” Howell says. Pal is explicit about the winners: technology and, crucially, crypto. He frames both as living within “log trend channels” that extend higher as cycles are elongated by policy engineering.

The 2021 crypto blow-off, in his telling, was a sunset cycle; this time, the extension lengthens the price runway. Gold also fits the mosaic, but with a twist in its driver set. Pal observes that gold has decoupled from real rates and is now “highly correlated with financial conditions,” poised to break from a wedge if the dollar weakens and rates ease.

Crypto stablecoins occupy a pivotal, and underappreciated, role in the architecture. Howell calls them a “conduit” for public-sector credit creation, while warning that deposits migrating from banks to stablecoins can curb traditional credit growth. Pal widens the lens: stablecoins are effectively a “fractionalized eurodollar market down to individual level,” giving any household in any jurisdiction access to dollar liquidity and, by extension, democratizing the demand base for US bills. It is not lost on either man that Europe is scrambling for its own digital-money answer, even if politics likely forces a central-bank-led route.

The risks now crowd the 2026–2027 window. The COVID-era terming-out of corporate and sovereign debt will need to be rolled in size at meaningfully higher coupons. Howell also flags a cash-flow squeeze emanating from the corporate capex boom: “US tech companies [are] currently investing, what is it, a billion dollars a day in IT and infrastructure… over a couple of years that’s going to take about a trillion dollars out of money markets.” That drains liquidity even as profits rise. His historical analogue is the late-1980s sequence—rising yields, commodities firming, a policy signal misread, then an abrupt liquidity turn that cracked equities. He is not forecasting a crash, but he is clear that “we’re nearer the end than… the beginning.”

For now, neither man is bearish on the next three to six months. Pal’s Global Macro Investor financial conditions index points to an expansion, and Howell expects “pretty decent Fed liquidity” to persist as authorities avoid repo stress and lean on duration management.

“Through year end… generally I think it’s okay,” Howell says. “We will get wiggles… but the trend is intact and continues for a while.” The operative phrase is his earlier one: steady as she goes—into the liquidity endgame. Crypto sits squarely in that cross-current, the prime expression of monetary inflation even as the calendar inexorably advances toward a refinancing test that will decide whether today’s engineered extension ends in a soft plateau or a sharper turn.

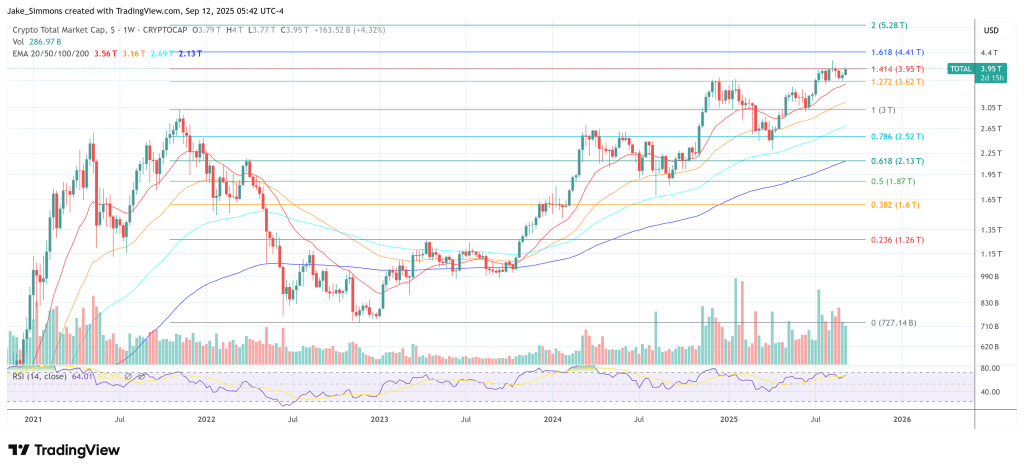

At press time, the total crypto market cap stood at $3.95 trillion.

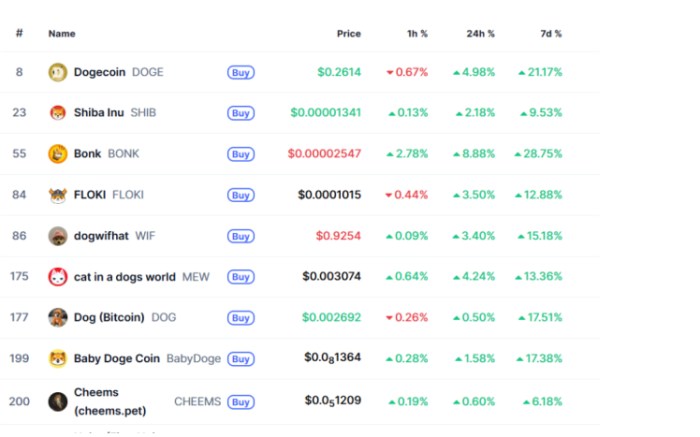

Expert Crypto Trader Says Dogecoin Price Looks ‘Very Good’, Here’s Why

An expert crypto trader shares a strong view on Dogecoin and the broader market, saying conditions l...

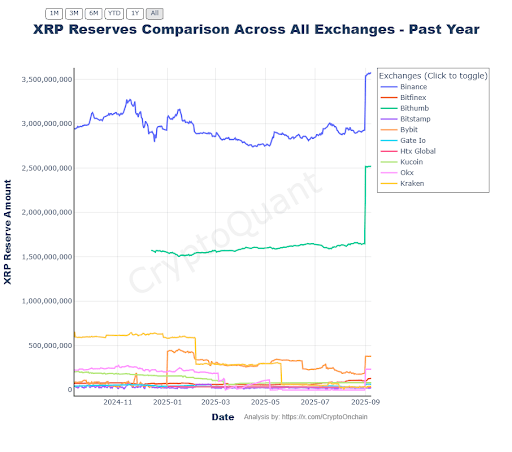

XRP Exchange Reserves Balloon 1.2 Billion In One Day, Why This Is Bearish For Price

XRP Exchange reserves have surged by 1.2 billion in just a day, presenting a bearish outlook for the...

Dogecoin Up 20% as CleanCore Buys $125M in DOGE —Maxi Doge Could Explode Next

Dogecoin has been steadily rallying, increasing nearly 20% to about $0.25, after a large purchase fr...